This week’s lesson from James can be a little discomforting. James pulls no punches when he addresses his readers: “Adulterers! Do you not know that friendship with the world is enmity with God? Therefore whoever wishes to be a friend of the world becomes an enemy of God” (James 4:4). Our initial read may assume that James is directly addressing someone guilty of adultery, but closer examination reveals that he is using adultery as a metaphor here for those that have a “friendship with the world”. Now before you think I am going to go off a tirade about how evil the world is and how we as Christians must flee from any interaction with the sinful, corrupt world, I want to put your mind at ease. I don’t think James is engaging in some kind of world-denying spirituality that would see the material world as inherently evil. Such a spirituality does not fit with the general direction of the biblical tradition nor with the sacramental spirituality of the church that says creation comes from God and is a means by which God may be known. Additionally, we can’t avoid contact with the world. The gospel of John has Jesus speaking to this relationship to the “world” when he says, “I am not asking you to take them out of the world, but I ask you to protect them from the evil one. They do not belong to the world, just as I do not belong to the world. Sanctify them in the truth; your word is truth. As you have sent me into the world, so I have sent them into the world” (John 17:15-18). So, what does James mean by “friendship with the world”?

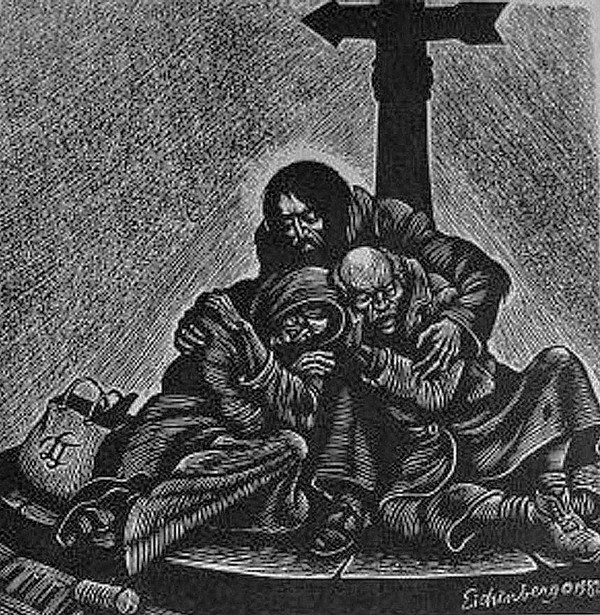

James seems more concerned here with values. James is addressing those who have allowed “bitter envy and selfish ambition” to rule. Those who pursue “friendship with the world” are more concerned with building themselves up in the eyes of others. When envy and ambition rule, all sorts of disordered behaviors spring from them: murder, disputes, and conflicts. James wants instead to encourage a “wisdom from above” in contrast to this “friendship with the world.” This wisdom has much different manifestations. Instead of disorder and wickedness, the wisdom from above produces purity, peace, gentleness, a willingness to yield, mercy, and the absence of partiality and hypocrisy.

A classic story that illustrates this difference between a “friendship with the world” and the “wisdom from above” is that of Cinderella. Many of us know the story of Cinderella both from childhood stories and the Disney production. Cinderella is a young girl whose mother has died and her father has remarried to a wicked step-mother who comes into Cinderella’s life bringing cruel step-sisters into the family. Cinderella is mistreated by her new step-family, a family which has an over-inflated sense of their importance. When the prince of the kingdom throws a ball and invites his subjects, the step-mother and step-sisters cannot imagine Cinderella being on the same level as they and manipulate the situation so that Cinderella is left at home while they proceed to their “rightful” places at the ball. They hope that the prince, upon seeing the obviously worthy step-sisters, will select one of these step-sisters as his wife and future queen, raising the family even higher in prominence to the place where they rightly belong. Cinderella is not even worthy of consideration.

To the rescue comes the fairy-godmother who pours out special favors on Cinderella to reveal her beauty and worthiness and to enable her to attend the ball. It is the humble Cinderella, now revealed in all her glory, who catches the eye of the prince. We know that the story does not end there, for Cinderella flees, leaving behind a precious slipper that the prince will now seek to use for the identification of his beloved.

When the prince comes looking for the owner of the slipper the step-sisters go to great lengths to prove their self-perceived worthiness, even to the point of engaging in self-mutilation to try to force their feet into the ill-fitting slipper. Their attempts at deception are uncovered and they are rejected by the prince. It is only when the prince discovers that it is the humble Cinderella whose foot fits the slipper perfectly that we arrive at the resolution of the story that can be labeled “happily ever after.”

The step-sisters are the antithesis of what C. S. Lewis may have meant when in Mere Christianity he defines true humility in the following way: “True humility is not thinking less of yourself; it is thinking of yourself less.” The step-sisters are models of envy and ambition, what James means by “friendship with the world”. This envy and ambitions drives the step-sisters to disputes among themselves and to their oppression of Cinderella. They have an inflated sense of their role in the world and are unable, or unwilling, to concede the value and nobility of anyone else. Cinderella’s humility, on the other hand, leaves her open to the gifts, may I dare say the graces, that prepare her for the ball and her eventual elevation as princess. It is Cinderella’s humility that is the key to her greatness. In some version of the story, Cinderella forgives her step-sisters and even arranges marriages for them to courtiers, thus revealing herself as “peaceable, gentle, willing to yield, full of mercy and good gifts”, a model of “wisdom from above.”

A similar story of ambition leading to conflicts and disputes is found in our gospel selection today. Jesus’ apostles are debating among themselves about who was the greatest. Jesus’ response to this conflict is fairly familiar, “Whoever wants to be first must be last of all and servant of all” (Mark 9:35b). Selfish ambition seeks only to lift oneself above others and the ambitious person does not care who she or he must step on in order to reach the top. Christian humility seeks to build others up as the servant of all.

So during this next week let’s flee from a “friendship with the world,” not in a way that denies the goodness of creation or God’s self-revelation through the created world. Instead let us flee from the ambitious desire to be seen as great in the eyes of others. In place of earthly, unspiritual, and devilish desires let’s embrace a wisdom from above that is “pure, then peaceable, gentle, willing to yield, full of mercy and good fruits, without trace of partiality or hypocrisy.” Let’s seek out ways to build each other up through mutual servant-hood, being humble, not in some self-deprecating way, but in a way that thinks of ourselves less often so that we may think of others more. It is in this humility that we will find ourselves open to the grace that God yearns to pour out on the humble.

Even to this day my mother calls my father and me to the kitchen table for dinner with “Get your ten little people washed. Dinner’s on the table.” It would almost seem that Jesus and the pharisees are having a disagreement about hygienic hand washing before meals, something that we would tend to accept as an obvious health measure. The debate, however, is over observance of certain ritual behaviors that have their root in the interpretation of the laws of the Torah rather than in the observance of a specific law or health practice.

Even to this day my mother calls my father and me to the kitchen table for dinner with “Get your ten little people washed. Dinner’s on the table.” It would almost seem that Jesus and the pharisees are having a disagreement about hygienic hand washing before meals, something that we would tend to accept as an obvious health measure. The debate, however, is over observance of certain ritual behaviors that have their root in the interpretation of the laws of the Torah rather than in the observance of a specific law or health practice. “

“